Struggling with structure

The power of understanding your story's timeframe

Craft: Assembling your story

Trying to figure out the structure for your book project is a lot like opening an IKEA flat-pack box for a cabinet unit and realizing they haven’t included the instructions for how to put it together. You think all the pieces are there. You lay them out on the floor, walk around them, look at them from different angles—and wonder how the fuck does it all fit together?

I wish structuring a project was as simple as downloading that missing instruction booklet from the website. Sadly, it’s not. And each writer will have their own strategies for navigating the task of structuring. For me, one of the keys—as essential as having the right IKEA allen key—is determining the story’s timeframe.

When does your story take place?

For projects with a strong narrative backbone (memoir, historical nonfiction, journalistic investigation among others), determining your book’s timeframe is crucial. And timeframe is not the same as the timeline.

What’s the difference? A timeline or chronology is simply listing events in the order in which they happened. Determining that timeline is an important step in researching any work of narrative nonfiction or in crafting a fictional narrative: you want to have a clear handle on what happened when. As I say to students, linear chronology is your friend. It doesn’t mean you can’t shake things up and tell a story “out of order”—but you as the author need to have a clear understanding of what the timeline is before you start mucking about with it.

So let’s consider the chronology or timeline of four different books:

Toufah: The Woman Who Inspired an African #MeToo Movement: In the book I co-authored with Toufah Jallow about her escape from The Gambia in 2015 after she was raped by the country’s then-president and dictator Yahya Jammeh, the timeline encompassed Toufah’s whole life, including some events that predated her birth (Jammeh’s coming to power; events in the lives of her mother, father and grandparents).

The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer: In my colleague Dean Jobb’s book, the timeline of the book was roughly the length of Dr. Cream’s life, from his birth in Glasgow, to the murders he committed in Canada, the U.S. and England, to his final capture and trial in London.

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity and Love: In Dani Shapiro’s memoir, the timeline of the book is roughly from the time of her parents’ marriage, their struggle to have a child and Dani’s conception/birth, through her life and decision to take a DNA test on a whim and the events that follow getting those results.

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars: In Francesca Wade’s group biography, there are actually five timelines, one for each of the five women she profiles. Each timeline follows that writer’s life, with the earliest beginning with the birth of Jane Ellen Harrison in 1850 and the latest stretching to the death of poet Hilda Doolittle (who wrote as HD) in 1961.

But the timeframe for each book differs significantly from the timeline for each:

Toufah: The timeframe runs from when Toufah decided to enter the presidential scholarship pageant in November 2014 to her life in Toronto and The Gambia in 2020.

The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The timeframe is 1892—the year of Cream’s capture and trial in London and the investigation of his past by the detective involved in the case.

Inheritance: The timeframe is roughly one year, from the time Shapiro does the DNA test to the resolution of her search for answers.

Square Haunting: The timeframe, as the subtitle of the book indicates, covers the period between the First World War and the Second World War, so 1916 to 1940, with each woman’s section focussed on the specific time during which she lived in London’s Mecklenburgh Square.

Here’s the thing, though: each book includes material from the chronology that sits outside the book’s timeframe. And each author could have chosen a different timeframe that encompassed more or less of that book’s chronology.

Confused yet? Let’s talk it through a bit more.

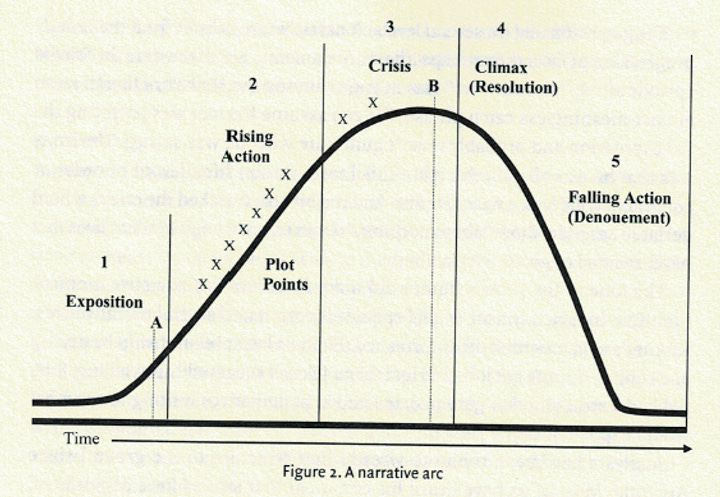

In Western storytelling traditions, a standard narrative arc is shaped like a wave viewed from the side, with action rising to a crisis point, followed by a climax or resolution to that crisis and then denouement or the tying up of the story’s ends. (Note that this is simply one way to tell a story: cultures around the world have different approaches to storytelling, and even within the Western tradition, there are other story structures. See the list at the end of this piece for resources to explore structures further.)

A standard Western narrative arc (illustration from Jack Hart’s book Storycraft):

One of the keys to creating propulsive story pacing is to keep the timeframe of the arc as tight as possible, because the tighter the timeframe, the steeper the climb.

Arc of Toufah timeframe if it encompasses her lifespan—lengthy, slow build:

Arc of Toufah timeframe, tightened to encompass key events from 2014-2020—steeper build so story pacing feels more urgent:

OK, so what do you do with all the stuff—the events and background you need to fill in to make sense of the story—that falls outside your tighter timeframe? That material gets woven into your main storyline as backstory and context. For instance, you might have a couple of pages detailing how Toufah’s parents met and married integrated into a section about Toufah’s homelife in 2014. And even within that section about how her parents met and married, you might have a few lines about her grandmother’s own early marriage.

In the case of material of more importance, you might have a section of flashback, taking the reader outside of the main timeframe and into the “past”—that is the past that predates the book’s timeframe. This is how I handled a lengthy section about Toufah’s brother Pa Mattar, who died in 2011 but who was an important influence on Toufah’s life. I inserted it as a flashback in the section of the book where Toufah was living in Vancouver and coping with depression, an emotional period that echoed emotions connected to Pa Mattar’s death years earlier.

Or, if, as in Square Haunting, you want to tell readers about what happens in the “future”—the period that follows your main timeframe—you might have a section focused on that future period (in Square Haunting, a short section at the end of the book titled “After the Square”) or a few paragraphs of “flash forward” within a section.

In all these cases, settling on your book’s timeframe allows you to know what your book’s “now” is, so that you are in clear coherent control of time shifts into your book’s “past” and “future.” In the case of Toufah’s story, the book’s timeframe is 2014 to 2020—the book’s “now.” Anything before 2014 is in the book’s past; anything after 2020 is in its future. For Dean Jobb’s book about Dr. Cream, 1892 is the book’s “now,” with events before that time in the book’s past and after that year in its future.

Sometimes, figuring out your timeframe also involves figuring out who is going to “tell” your story. In a lecture to students in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College, my colleague Dean Jobb talked about how in an early draft of The Murderous Dr. Cream, the timeframe of the book was much broader—essentially Cream’s lifetime told in a linear chronology. But Cream’s story is complicated: he murders in three different countries, he ends up in jail in America for a lengthy period, he’s released and goes to London where he quickly starts killing again and is arrested and put on trial in fairly short order. Told over that lengthier timeframe of Cream’s life, the story has a lot of stops and starts—it’s a series of shorter though building waves. Dean credits his editor Amy Gash at Algonquin Books with suggesting that he tighten the timeframe to Cream’s time in London in 1892, pointing out the possibility of using a character as a kind of stand-in for the reader: a real inspector who set out to investigate Cream’s earlier life in preparation for the trial. By using that investigation as an organizing framework, Dean was able to tighten his timeframe for the book to 1892, but still weave in all of Cream’s earlier life and crimes as discovered by the inspector. The result? A gripping, urgent read that tells the story of a single year in Cream’s life—but works in all the context and backstory of Cream’s earlier crimes.

So how might this apply to your project? Screenwriters talk about starting scenes late and ending them early. The same might apply to determining the timeframe of your narrative: what’s the latest point at which you could start your story, and the earliest point at which you could end it?

Instead of a lifetime, a decade

Instead of a decade, a year

Instead of a year, a season

Instead of a season, a month

Instead of a month, a week

Instead of a week, a day

A day many not be long enough to tell your story: the point isn’t to simply choose the shortest timeframe, it’s to choose the one that best suits your material and overall storytelling goals.

But what if my book doesn’t have a natural narrative arc?

I’m working on a project now with a co-author where the book, as originally conceived, didn’t have a natural narrative arc. There are many narrative sections within the book, describing incidents from my co-author’s life and the lessons and insights she’s drawn from those experiences, along with psychological, scientific and medical studies that relate to those lessons and insights. As we worked on the book, it became clear the book needed a lightly drawn narrative thread to link the chapters. Our editor referred to it as the “frame narrative,” and suggested we consider using a road trip my co-author had taken as that frame narrative. We’d referenced the road trip—during which she’d come to some important decisions about her life—a few times in the book but hadn’t included it consistently through the chapters. At the editor’s suggestion, we did a deeper dive into the trip, and used additional scenes from it to open each chapter and lead into the various themes of the book. The manuscript isn’t finished yet, so this may still change—but for now, that trip has become a thread that readers follow through the book, while also leaving room to weave in other stories and experiences from her life.

For those working on nonfiction “idea” books, it can be useful to think about whether it’s possible to create a narrative frame—and with it, a timeframe—for your book. In wrestling with the ideas you are exploring, perhaps you spent a summer writing and thinking at a cabin in the woods. Or struggled through a single school year with your child. Or spent a week dealing with a crisis at work. Ideally, you’re seeking a narrative frame that links in some natural or resonant way to the idea you’re exploring. Sometimes this narrative is embarked on expressly to probe your “big idea”—you decide to change your life by saying ‘yes’ (Year of Yes by Shonda Rhimes); you explore faith and its 21st-century relevance by following the bible’s advice for a year (The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs); you follow the advice of self-help books to see which ones really work (By the Book podcast).

Or, as J.B. MacKinnon does in his book The Day the World Stops Shopping, perhaps you create what MacKinnon calls a mind experiment. MacKinnon wanted to explore questions around over-consumption and its environmental impact, and so he posed a question: What would happen if the world stopped shopping? Answering that question took him to scenes and experts around the world as he tried to unravel what a world without shopping would look like, grappling, along the way, with a real-world interruption in consumption as the pandemic dramatically slowed global consumption—at least for a time.

And there are other ways in, too

The traditional Western narrative arc isn’t the only way to tell a story. You might braid a story, with two alternating storylines. You might circle an idea, looking at it from multiple perspectives. You might impose an existing format (a recipe, an advice column, an instruction manual) to reveal another layer of your story’s truth by going the “hermit crab” route. Your culture may also have unique structures and storytelling approaches. Some resources if you’re intrigued and want to explore further:

Traditional Western narrative arc

Writing for Story: Craft Secrets of Dramatic Nonfiction by Jon Franklin (book)

Storycraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction by Jack Hart (book)

Western variations

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process by John McPhee (book)

Alternative structures

The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms edited by Kim Adrian (book)

Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative by Jane Alison (book)

The Far Edges of the Fourth Genre: An Anthology of Explorations in Creative Nonfiction edited by Sean Prentiss and Joe Wilkins (book)

Enlarging the possibilities

Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers, edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton (book)

How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill, edited by Jericho Brown (book)

Diversity Plus: Diverse Story Forms and Themes, Not Just Diverse Faces by Henry Lien (article)

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin (essay)

Writers on their structures

Index Cards for Story Structure: Rebecca Skloot on structuring The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (video)

Screenwriter Dustin Lance Black on structuring his screenplays (video)

Exercises

Tighten the frame: As you look at the timeline of your story, consider the most dramatic or pivotal scene. How tightly can you zoom into that scene and the events leading up to it? Is there enough material to sustain using that tighter timeframe as your main narrative structural line—to use that timeframe as the beginning, middle and end of your story? It will depend on a number of factors: the amount of detail you have to work with; the projected length of the finished narrative; the character you’re focusing on to tell your story. For a magazine-length narrative, you might be able to tighten the timeframe of a profile of a baseball pitcher to a single game. For a book-length narrative, your timeframe might need to shift to a full season of play.

Shift the lens: List your characters and your key points of action. Who in your character list has the ability to see much or most of the action—or has access to ways of telling parts of the story they didn’t personally witness? Maybe that business story you’re telling can be told through the eyes of the daughter of the founders who has to wind down the business, rather than the parents who launched it—and that might suggest a different timeframe for the narrative.

Look for a model: Got a story, movie or podcast that’s a fave? Go back to it as a writer rather than simply a reader or listener and deconstruct it. Chart its timeframe. Draft a chronology/timeline for the story. Consider the story from the perspective of secondary characters and think about how it could be retold through their eyes. What insights can you take from unraveling this structure to apply to your project?

Choice words

Things I’ve underlined this month (yup, I am a chronic defacer of my books):

“It takes some courage and imagination to aspire to an invigorating life, rather than a happy or a successful one... Today, we speak about ‘having it all,’ perpetuating an unattainable ideal of achievement and fulfillment: still, women talk anxiously of how to reconcile their personal lives and careers, of the toll taken by refusing to conform to persistent narratives of how to live, echoing concerns little changed from a century ago....None of these women [in Square Haunting] is a straightforward role model by any means, yet in researching their lives I’ve been reminded how knowledge of the past can fortify us in the present, how finding unexpected resonances of feeling and experience, across time and place, can extend a validating sense of solidarity. In placing these lives together, I’ve been particularly struck by small moments which have shown how these figures, too, were quietly bolstered by the examples of other women—including, in some cases, each other.” Square Haunting by Francesca Wade, pp 318-319

“...the question to ask as a writer is What do our characters want and how are they going to get it? Always. Why? Because it’s the question we’ve been asking ourselves our whole lives.” Jacqueline Woodson, “What Do You Want from Me” in How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill, p. 27

“Focus on that slice of your life that haunts and inspires you. ...Writing a memoir forces you to take ownership of the story of your life. Ownership means claiming your life and all its false starts and final reckonings. ... Writing a memoir means being prepared to evaluate your life and to uncover its terror and its grace.” Marita Golden, “How to Write a Memoir or Take Me to the River” in How We Do It, pp 45-46

And if you would like a master class in character description, you could learn much from Charlotte Gill’s deeply thoughtful, richly drawn memoir Almost Brown: A Mixed Race Family Memoir. The chapter-long description of her father that begins the book is complex and compelling; her mother too is brought vividly to life; and Charlotte doesn’t forget to paint herself into the picture as well, with language that is lively, muscular and funny:

“My twin and I were violently exuberant kids, fueled on a newfound cornucopia of American junk food. We expressed our energy though physical means, wrestling and even brawling whenever sibling rivalry demanded it. All through the house the drywall was pocked with doorknob holes because that’s what we did. We destroyed things. We were doctor’s children, with no respect for delicacy, or the hard-won cost of nice things. We gravitated toward fragile objects with a hungry sense of demolition, proving early that our parents’ taste for slender-legged antiques and cream-coloured upholstery had been a terrible idea.” p. 59

Other stuff

How to get interviewed on podcasts: A guide for book authors from Scribe Media

Writer Rebecca Makkai on endings—a 6-part Substack post on story endings

Writing the Other online courses—an excellent selection of courses on various aspects of diversity in storytelling

Obligatory photo of Buddy, and introducing Reggie

Reggie, an 11-year-old orange puddle of a cat, has joined our family. Buddy would like to be Reggie’s best friend. Reggie is still interviewing Buddy, and has not yet made a decision on whether Buddy will be getting the job.

The stuff at the bottom

I’m a writer, editor and teacher. This is my personal e-newsletter on the craft of writing nonfiction, sprinkled with occasional feminism and social justice. You can find out more about me on my website at kimpittaway.com. You can also find me on Facebook. I’m a cohort director in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction limited residency program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. If you’re interested in writing a nonfiction book, you should check our program out! (And hey, we just added a limited residency MFA in Fiction as well, taught by some of my amazing colleagues!)

And finally

Share your online course and community recommendations, links to cool things writers and other creative folks are doing and whatever else strikes you in the comments section of the web version of this post. And feel free to share this email with anyone else you think might be interested in it.

This'll keep writers busy for a while. It's a whole workshop in a post. I didn't make any progress with structure until I started using Scrivener, which made it easy to see the manuscript at a glance and weed out every chapter that added nothing new to the story.

Kim, you make clear something that seems extremely complicated and frustrating when floundering in the weeds of the early drafts. I've wrestled with structure for every one of my books without knowing exactly what was wrong or what was needed to fix it. This is very helpful. Time to start a new one.