Yes, it’s true: I am an irregular poster. I hope, as I materialize in your in-box in chilly February, that we both feel the warmth of reconnection.

In this issue, I’m focusing on bringing sound to the page. At the end of this post, you’ll also find information about an exciting workshop I’m taking part in; the release of Unconditional, my co-authoring collaboration with Dr. Samra Zafar; and some hints about other upcoming activities. I’d love to hear what you’re up to as well: if you have courses or workshops you’re offering, new books out, essays or reviews published or simply thoughts and reflections on writing, please pop them into the comments. And please pass this email along to anyone you think might enjoy it as well.

Craft: Sound garden

This week, I spent 32 minutes with a soundscape ecologist, and I’ve spent hours since thinking about what I heard.

The 32 minutes was in the form of a short film, The Last of the Nightingales, by Masha Kapoukhina for The New Yorker.

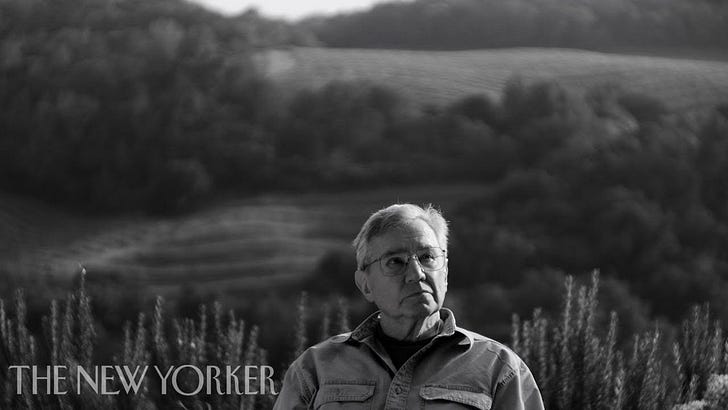

The soundscape ecologist is Bernie Krause, who began his career as a sound engineer in film (notably being hired and fired eight times while working on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now) before discovering his true calling: recording sound in natural environments, from forests to coral reefs to glacier fields. Krause has, since the mid-1970s, accumulated thousands of hours of recordings, often returning to the same spots years apart, allowing him to compare how sound ecosystems have changed over time, revealing changes in the environment that aren’t always evident to the eye. In some cases, a forest looks unchanged and yet the birds are quieter. Why? Perhaps key old growth trees have been selectively harvested, disrupting nesting, or climate change means that mating season has shifted weeks earlier. In other cases, the buzz of insects has softened, a sign of the loss of some 70 per cent of insects in the last decades. Below the sea, the static-like noise of a healthy coral reef recedes almost completely so that only the low whoosh of the current is audible, a signal of the reef’s decline.

There is a twist late in the film that I’m not really spoiling, since it’s conveyed in the online label attached to the film and its YouTube description: Krause and his wife Katherine lost their home and all they owned in a California wildfire, bringing the impact of the environmental change they’d long heard happening literally to their doorstep. It’s a deeply moving, well-told story of a life spent listening, with a compelling message about what Krause has heard and wants us to hear.

In my last post, Story Sense, I talked broadly about using sensory details to bring stories to life. In this post, inspired by Krause’s story, I want to focus specifically on sound.

What’s that sound?

“Get the recorder!” When my sister Tina and I worked together on a couple of radio documentaries, I got a crash course in painting pictures with sound. It helps to have an award-winning radio producer in the family, and while I’d watched her work on her own stories for years, it wasn’t until I worked alongside her that I really listened to the sounds that bring listeners inside a radio or podcast story. Together, we produced “Tina and Kim’s Watery Road to Hell” about our home’s water use, and along the way, I learned that water roaring full-blast from a kitchen tap into an echoing metal sink sounds distinctly different from a summer downpour’s fat drops slapping steamy pavement and cascading along an overflowing gutter, that the thunk-thunk-thunk-click-ratchet of a lawn sprinkler sounds altogether different from the soothing spray of a shower head against the bare skin of your throbbing back.

But even then, I didn’t consider how those sounds have shifted over time: that full-blast from my 21st-century pull-down faucet sounds different than full-blast from the washerless tap of my childhood kitchen, with its hiccup of air and barely regulated burp of water tumbling into the sink; that fat drops on paved urban parking pads land with a splat altogether different from the sploosh of rain on the gravel driveways I grew up with, and cement-curbed gutters whoosh while country ditches gurgle.

The specificity of sound matters: it matters when we are recreating scenes from our own memories, when we are interviewing others about theirs, and when we may be tempted to cast a scene with sounds from our own experiences rather than considering how what we’re familiar with might be different from what actually was: a different time, a different geography, a different environment and perhaps most crucially, a different set of ears. Not only may I not hear what you hear, but even standing side by side, we may experience it differently. My mother has hearing aids, and she often reminds me that it takes her an extra beat for her brain to process the sound transmitted from device to her ear—that she’s had to in effect learn to hear in a different way from how she used to hear, from how I hear. I have tinnitus, and so a persistent low hum, like electrical wires or cicadas, underscores the sounds I hear. I know people who are super-sensitive to sound: their brains don’t ignore sound as easily as others might, making them great at noticing a shift in sound but causing challenges in trying to not notice sound altogether.

Consider:

What is the sound’s “when”? If the sound is not contemporary, what factors might influence the shape of that sound? What background sounds might have been there that aren’t there now—or would have been absent that we are used to? This is where the insights of sound ecologist Krause are so informative and important. What would people’s experience of sound been during that time? I live in a city where a noon-day cannon goes off every day. It still startles me sometimes, but would be even more fear-inducing if all I’d ever heard were natural sounds. Me now compares that cannon to a truck backfiring. Me of two centuries ago might compare it to thunder. If the sound is contemporary, can you expose yourself to the sound in real time to take notes about it? Can you capture the sound phonetically? Descriptively? Metaphorically?

Who is hearing? The same sound can prompt vastly different associations for people of different backgrounds, and so as writer, your word choice should reflect that—or if you’re subverting that, it should be deliberate and not accidental. A jet flying low overhead means vastly different things to someone whose experience of aircraft comes from airshows versus someone whose experience comes from war zones. Even within cultures and communities of similar backgrounds, how old a person is or other factors might that affect their experience of the sound.

As you research:

Look for sidenotes: If you are doing historical research, look for references to sounds embedded in other documents—letters, news stories, journals may all include information about sound even when sound is not the primary subject of the document.

Just ask: If you are interviewing people about past experiences, ask about sound. It can be tough to get people to put themselves into the past, to draw up those past sensory experiences. Some things to try:

Ask the person to think of a specific scene and then to describe it in the present tense. Not “I walked down the hall” but “I’m walking down the hall...”

Ask the person to think of a specific place in the past, and in their minds, to sit down in the middle of it, draw a few breaths, and rather than describing what they see, to describe the setting entirely through their other senses.

Hit record: If you are doing contemporary research, pull out your phone and record some sound. Even when it’s “quiet” you’ll be surprised at what you might hear later when you review the recording.

As you write:

Sound it out: Think about how the sounds of the words you choose reflect, contradict or magnify the soundscape you are trying to create on the page. Onomatopoeia is the technical term for words that echo the sounds of the thing they are naming. Clunk, oink, chirp, meow are obvious examples. Many bird names are onomatopoeic, with their names echoing their calls: cuckoo, chickadee. Sometimes it’s helpful to capture a sound phonetically—trying to “spell it out” on the page, even if what you’re left with is a made-up word. Other times, you can use sounds in your sentences to create connections or echoes of the sounds you’re invoking. Author and writing teacher Geraldine Woods stretches the term to encompass the overall sound of an author’s sentences in her terrific book 25 Great Sentences and How They Got That Way. Her chapter on onomatopoeia is packed with examples—for instance, from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” where Coleridge uses the reader’s own breath pushing out “f” sounds to echo the sound of water rushing past a ship’s hull: “The furrow followed free...” (I highly recommend Woods’ book, both for her wide-ranging examples and for the great writing exercises she includes to expand your range of writing techniques and tools.)

Add some muscle: As noted in my post Story Sense, you may be tempted to resort to adverbs and adjectives as you try to describe your soundscape. Back up, pluck your verbs from the page and examine them closely: Are they precise? Descriptive? Are they creating images, embodying action? I could have simply said “Look are your verbs.” But “Back up, pluck your verbs from the page and examine them closely” uses more descriptive verbs to create a word picture of a series of actions. It pushes you to embody what might otherwise be an entirely mental exercise, and I would argue that embodiment makes the process clearer and the prompt “stickier”—you’ll remember it better.

Get emotional: Can you use a metaphor or a story to evoke the emotional impact of the sound? One of my favourite examples of this comes not from descriptions of sound, but from descriptions of scent. Authors Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez wrote a book of over 1,800 perfume reviews, described by the New York Times as “ravishingly entertaining.” But think of the task: how do you describe 1,800 different perfumes in a way that both differentiates them and makes readers want to read on? Yes, in Perfumes: The A-Z Guide, Turin and Sanchez described specific notes in the scents—this one has coffee and burnt sugar, that one has jasmine and rose—but what made the book so successful was that they masterfully described the emotional resonance and impact of scents, sometimes in ways that were deeply personal and unique to them but which ultimately still connected with readers. For Cabochard, a once-great perfume that has been diminished by the substitution of cheaper ingredients over time, Turin wrote: “I remember ten years ago sitting on the London Underground opposite Peter O’Toole. Despite the white suit and the cigarette holder, nobody seemed to recognize him. This Cabochard is much the same: ravaged by years of abuse, gaunt, bleary-eyed, prematurely aged, heartbreaking to those who knew [perfumer] Bernard Chant’s masterpiece in its heyday. ...This is Cabochard chewed down to a frazzle by accountant moths.”

Exercises

1. Make some noise: Take a scene you’ve already written and inject sound into it. Return to your research with the goal of isolating sound cues. None there? What additional research can you do to allow you to layer in sound? If you are writing from your memory or personal experience, return to the scene—in real life or memory—and pay attention to the sounds around you. Can you describe the scene using only sound?

2. Exercise your ears: Over the next week, choose three different times and places to sit and listen for ten minutes. Hit record on your phone to capture the sound. At the same time, take real-time notes describing the sounds. Later, listen to the recording as you review your notes. Did you miss anything notable? Use both your notes and recording to write a short scene describing each of your three soundscapes.

3. Focus on the emotion: Using the example of the perfume description above, describe the emotional impact of a sound through metaphor or story.

Resources

1. Sound archives: Artists, audiophiles, radio producers, archivists, librarians and other sound enthusiasts have created a wide range of online sound archives and resources. Looking for sound inspiration or confirmation of what you think that sound you remember really sounded like? Check out Cities and Memory (explore “Obsolete sounds” under the Projects tab for some blasts from the past); US Library of Congress audio recordings ; Library and Archives Canada Music, Films, Video and Sound Recordings and Film, Video and Sound Database ; UK Imperial War Museum Sound Archive ; BBC Sound Effects ; Cornell University Wildlife Archive. Find more by searching “sound archives” along with any other descriptors associated with your specific needs, for instance “sound archives whales.” Also: note that “sound effects” may be different from “sound archives.” Sound effects may include manufactured sounds—that is, audio created to sound like something, for instance coconut shells rhythmically thumping on a wooden board to create the audio illusion of horse hoofs clomping down a street. If you are trying to describe a sound, look first for an actual recording of that sound, not a recreated version of that sound. (The BBC link above includes both actual sounds and special effects sounds.)

2. 25 Great Sentences and How They Got That Way by Geraldine Woods. Maybe it’s because I’m a word nerd, but this is currently my bedtime reading and I couldn’t be enjoying it more. Highly recommend.

3. A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide to Understanding and Writing Poetry by Mary Oliver. I think this is out of print but it is available as an e-book and you can also find it second-hand. Whether you aspire to write poetry or not, poets have much to teach us about how words sound on the page, and Mary Oliver’s slim guide is packed with insight and advice.

Courses and other stuff

Women on the Page—Writing women’s lives in memoir, biography, fiction & essays: I am delighted to be part of a 6-weeks writer-led online series of classes focused on writing women’s lives. In each session, an author will take you through her process: what did it take to get her book from idea to manuscript to published page? Along with author-teachers Gloria Blizzard, Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Lezlie Lowe, Wanda Taylor and Gillian Turnbull, we will explore the myriad ways of getting women’s lives onto the page in both nonfiction and fiction, with plenty of insights and guidance along the way. Plus a bonus session with literary agent Marilyn Biderman! Whether you’re a beginner, a published author or an enthusiastic reader, come join our circle. Find out more at www.womenonthepage.com

Just out—Unconditional: I’ve spent a significant chunk of the last two years working with Dr. Samra Zafar on Unconditional: Break Through Past Limits to Transform Your Future. In it, she explores the “unlearning” she had to do to move forward from past trauma and break free from beliefs that held her back, and how readers can too. It’s packed with insights, compelling personal stories, and workbook sections where readers can explore their own journeys. Samra is an inspiring guide for anyone seeking to live a life truer to who they are meant to be.

An experiment or two: Later this spring, I’ll be embarking on some experiments. One is publication-oriented: sharing a project I’ve worked on for some time but haven’t found quite the right home for, so I’ve decided to do something a bit nontraditional. I’m still sorting out the details, but for now will simply say—watch this space. I’m also developing an exploration of getting unstuck on a piece of writing, so if you’ve got something you’ve worked on, gone back to, stuck in drawer but never quite finished, this might be something we can explore together. Details on this to come later in the spring as well.

Buddy says hi

The stuff at the bottom

I’m a writer, editor and teacher. This is my personal e-newsletter on the craft of writing nonfiction, sprinkled with occasional feminism and social justice. You can find out more about me on my website at kimpittaway.com. You can also find me on Facebook. I’m a cohort director in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction limited residency program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. If you’re interested in writing a nonfiction book, you should check our program out! (And hey, we also have a limited residency MFA in Fiction as well, taught by some of my amazing colleagues!)

Information packed and inspiring. Thank you, Kim.

Thanks again for a wonderful and informative post. I learn so much and get to apply to my own writing. Really appreciate the work you put into these posts.